The Hidden Japanese Food Culture in Princess Mononoke's Dining Scenes

I'll be honest – whenever I watch a Studio Ghibli film, there's always that one moment where my stomach starts growling. You know what I'm talking about, right? Whether it's Howl's bacon and eggs or those giant steamed buns in Spirited Away, Ghibli food just hits different. But here's the thing about Princess Mononoke – the food scenes aren't about making you hungry. They're about something much deeper.

Today I want to dig into how these seemingly simple eating scenes in Princess Mononoke actually reveal profound insights about Japanese traditional culture, humanity's relationship with nature, and what these moments might mean for us living in the modern world.

Ashitaka and Yakul: True Coexistence

Remember that scene early in the film where Ashitaka shares his meal with Yakul, his red elk companion? What struck me was how Ashitaka gives Yakul food first, then eats himself. And they're eating the exact same thing.

Now, we typically give our pets their own special food, right? Dog food, cat food – we've created this whole separate category. But in the Emishi tribe's worldview, humans and animals are complete equals. Sharing the same food isn't just about feeding your animal companion; it's acknowledging them as a fellow living being worthy of the same sustenance. In this brief scene, Miyazaki shows us what genuine coexistence with nature could look like.

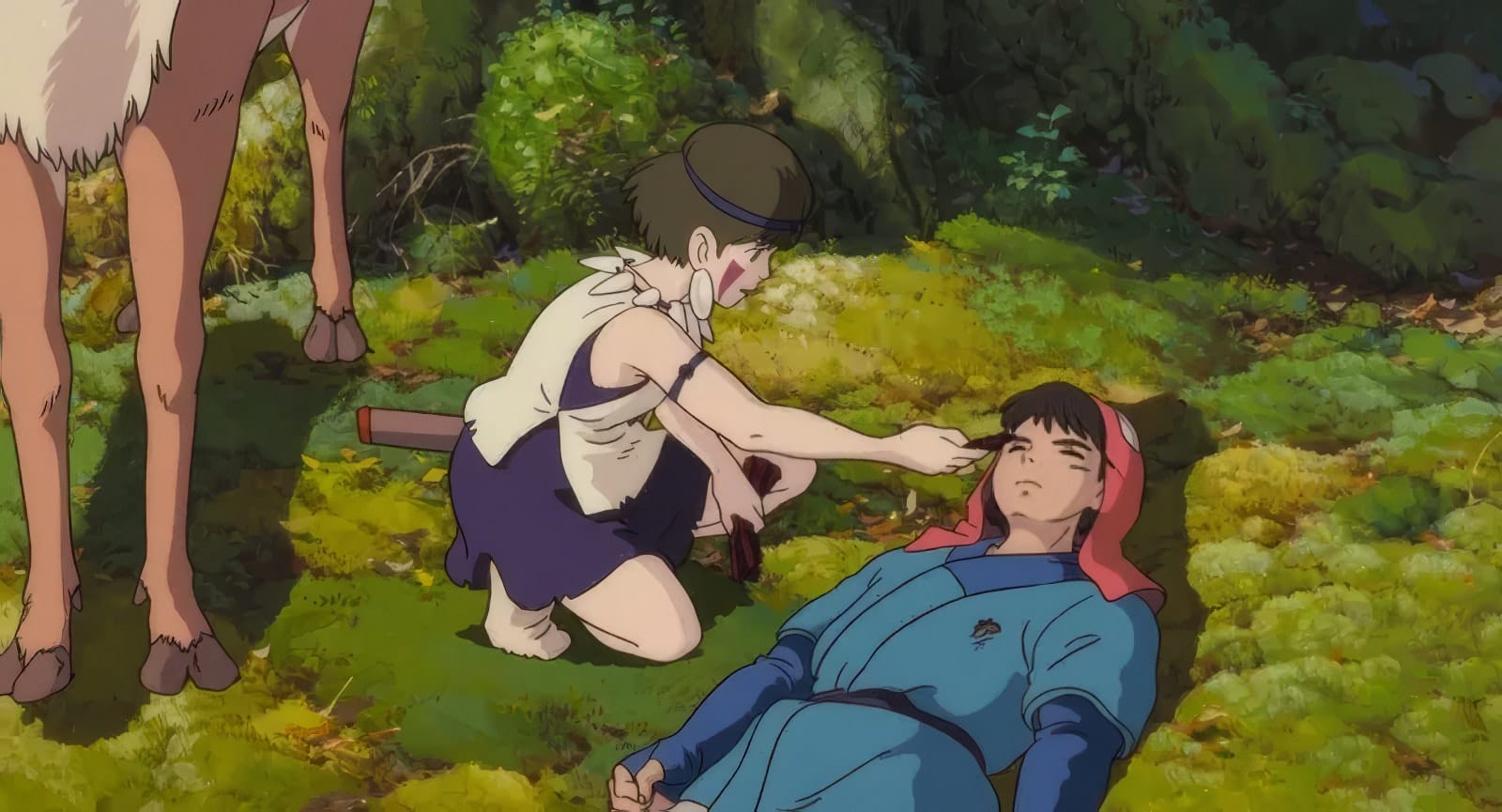

San's Primal Act of Care

Okay, let's talk about that scene. You know, the one where San chews up dried meat and transfers it mouth-to-mouth to a weakened Ashitaka. I remember watching this for the first time and feeling... confused? Shocked? But also strangely moved.

For San, raised by wolves, this is the most natural way she knows to care for someone who can't feed themselves. It's primal, yes, but also deeply intimate. This girl who claims to hate all humans performs this act of raw compassion that transcends species boundaries. When Ashitaka sheds tears of gratitude, we understand that genuine care doesn't always come in familiar packages. Sometimes it looks nothing like what we expect.

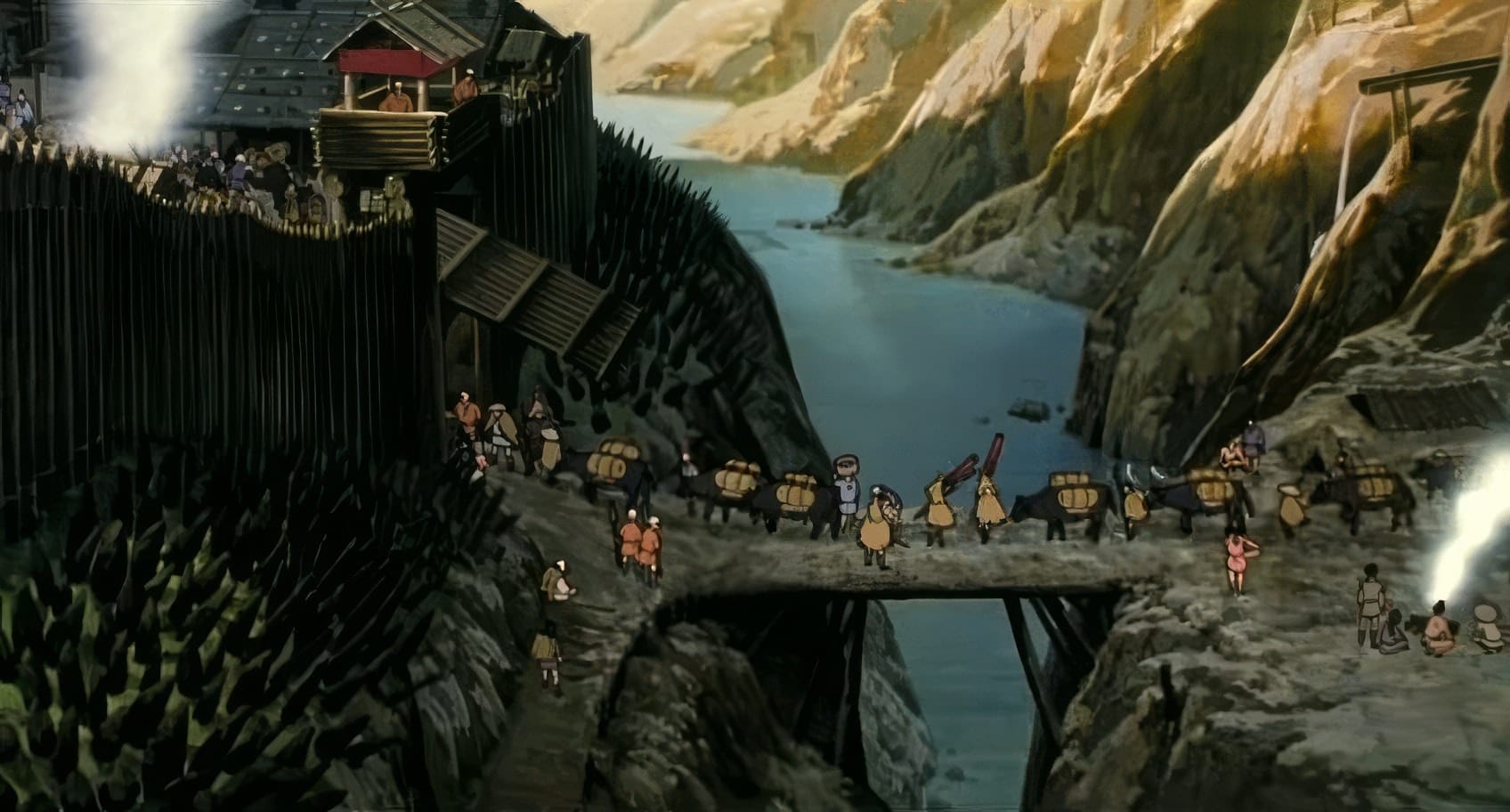

Rice in Iron Town: A Matter of Survival

"Get this rice home quickly so we can eat it soon," Lady Eboshi tells her people. Such a simple line, but it reveals so much about life in Iron Town. Despite all their industrial advancement, food security remains their primary concern. Someone complains about their meal, wondering if it's "soup or just water" – and suddenly we see the harsh reality of frontier life.

These scenes create such a stark contrast with our modern abundance. Food isn't just something to consume; it's the thread holding the entire community together, the difference between survival and starvation.

The Muromachi Period: When Everything Changed

Princess Mononoke is set during the Muromachi period (1336-1573), a fascinating turning point in Japanese history. This was when Japan began transitioning from living harmoniously with nature to attempting to dominate it.

A Tale of Two Tables

The class differences in diet during this era were staggering. Samurai enjoyed polished white rice and sake, eating three meals a day. Buddhism officially prohibited meat consumption, but they'd sneak wild boar and deer by calling them "mountain whales" (I mean, come on, that's kind of hilarious).

Meanwhile, 80% of the population – the farmers – had to give their rice away as taxes. They survived on millet, barley, and buckwheat. When times got really tough? Tree bark, wild plants, even insects. This massive inequality plays out in Princess Mononoke through the conflict between Iron Town and the forest.

The Art of Shojin Ryori

During this period, Buddhist vegetarian cuisine called shojin ryori flourished. This wasn't just about avoiding meat – it was a sophisticated culinary philosophy balancing five colors (green, yellow, red, black, white) and five flavors (sweet, sour, salty, bitter, umami). Can you imagine the skill required to create complex, satisfying meals using only plant-based ingredients, tofu, and seaweed broth?

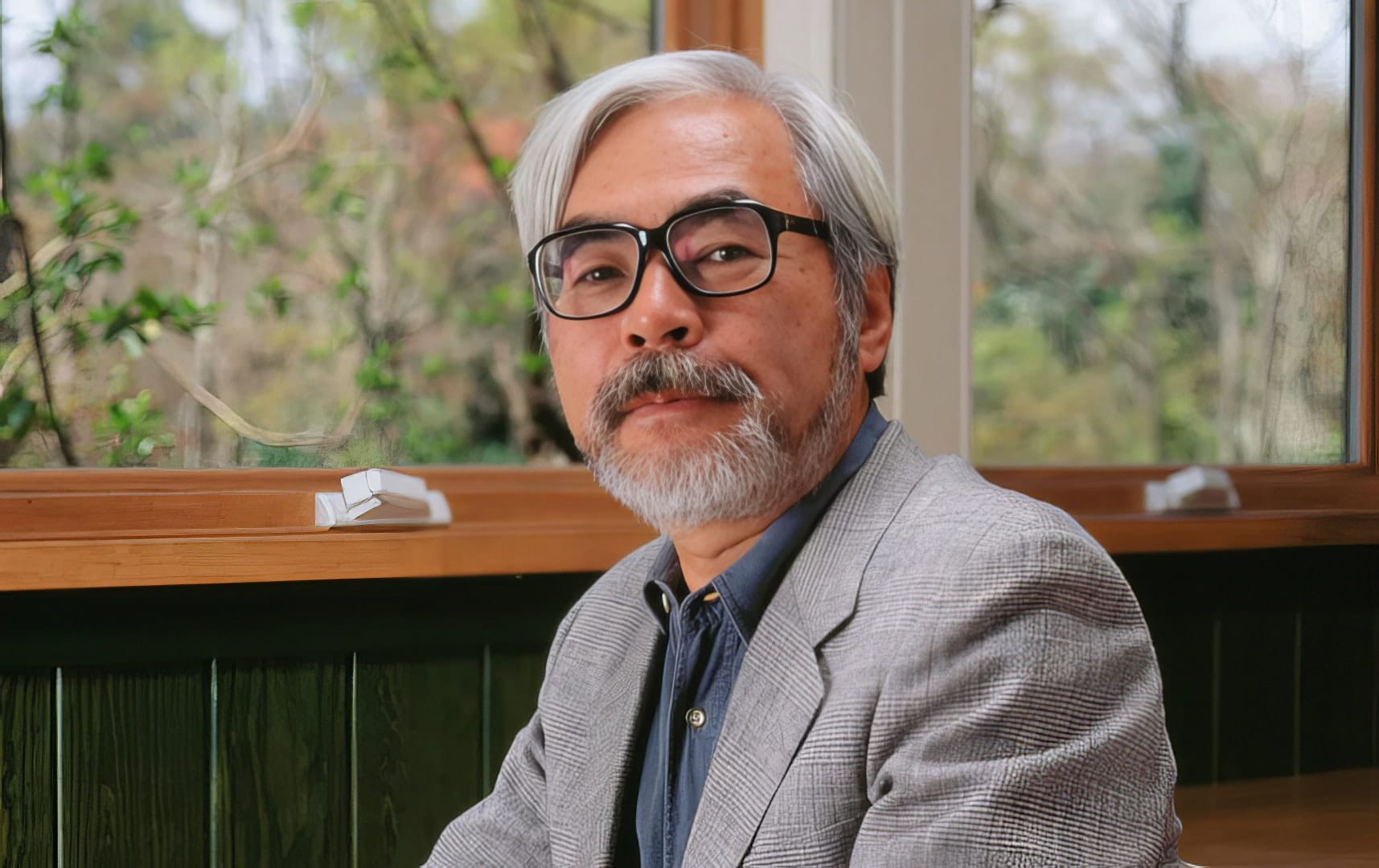

Miyazaki's Philosophy of Food

Here's what really gets me about Miyazaki's approach. Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki revealed that the director actually cooks every single dish that appears in his films. Every. Single. One. That's commitment, folks.

But there's something even deeper at play here. Miyazaki uses food scenes to create what he calls "ma" – the space between actions. He explained it to Roger Ebert like this: "The time between clapping is ma. If you just have non-stop action with no breathing space at all, it's just busyness. But if you take a moment, then the tension can grow into a wider dimension."

Princess Mononoke's food scenes serve as these meditative moments. They let us reflect on character relationships, process complex themes without exposition, and connect with the universal human experience of nourishment and care.

A Wartime Generation's Perspective

Born in 1941, Miyazaki experienced WWII rationing and food shortages as a child. He watched his father profit from running a munitions factory while civilians starved – a contradiction that clearly shaped his worldview.

This experience shows up in his work as detailed appreciation for abundance, anxiety about waste and excess, and emphasis on simple, wholesome meals. The food scenes in Princess Mononoke aren't just about nutrition; they're about survival, community, and our relationship with the sources of our sustenance.

Civilization vs. Nature on a Plate

Princess Mononoke uses food as a lens to show clashing worldviews. Ashitaka's tribal culture shows harmony through shared meals with animals. Iron Town's agricultural system represents humanity's drive to dominate and control nature. The forest dwellers' wild foraging shows a direct, unmediated relationship with nature.

Through these contrasts, Miyazaki explores the complex relationships between sustainable traditional practices, destructive industrial agriculture, and wild foraging that might not scale sustainably. It's not black and white – it's complicated, just like our real relationship with food and nature.

The Deeper Roots of Japanese Food Culture

Rice as Identity

In Japanese, "gohan" means both rice and meal. That's how central rice is to Japanese identity. Introduced around 400 BCE, rice cultivation transformed Japan from a hunter-gatherer society to an agricultural one. Mythology says the sun goddess Amaterasu invented rice farming. For over 1,500 years, rice has been offered at Shinto shrines. Even today, many Japanese consider it disrespectful to leave even a single grain uneaten.

The Philosophy of Seasonality (Shun)

Shun is about consuming ingredients at their absolute peak – not just for practical reasons, but for aesthetic, spiritual, and environmental ones. Traditional Japanese cuisine divides the year not into 4 seasons but 72 micro-seasons. Master chefs maintain encyclopedic knowledge of when specific fish, vegetables, and other ingredients reach perfection. This seasonal consciousness connects human consumption patterns with natural cycles.

Mottainai: The Regret of Waste

Mottainai expresses deep regret over wasting anything with inherent value. Rooted in Buddhist interconnectedness and Shinto respect for natural spirits, it transforms resource consciousness into moral practice. Despite modern Japan's food waste issues, grassroots movements actively promote mottainai values, showing its continued cultural relevance.

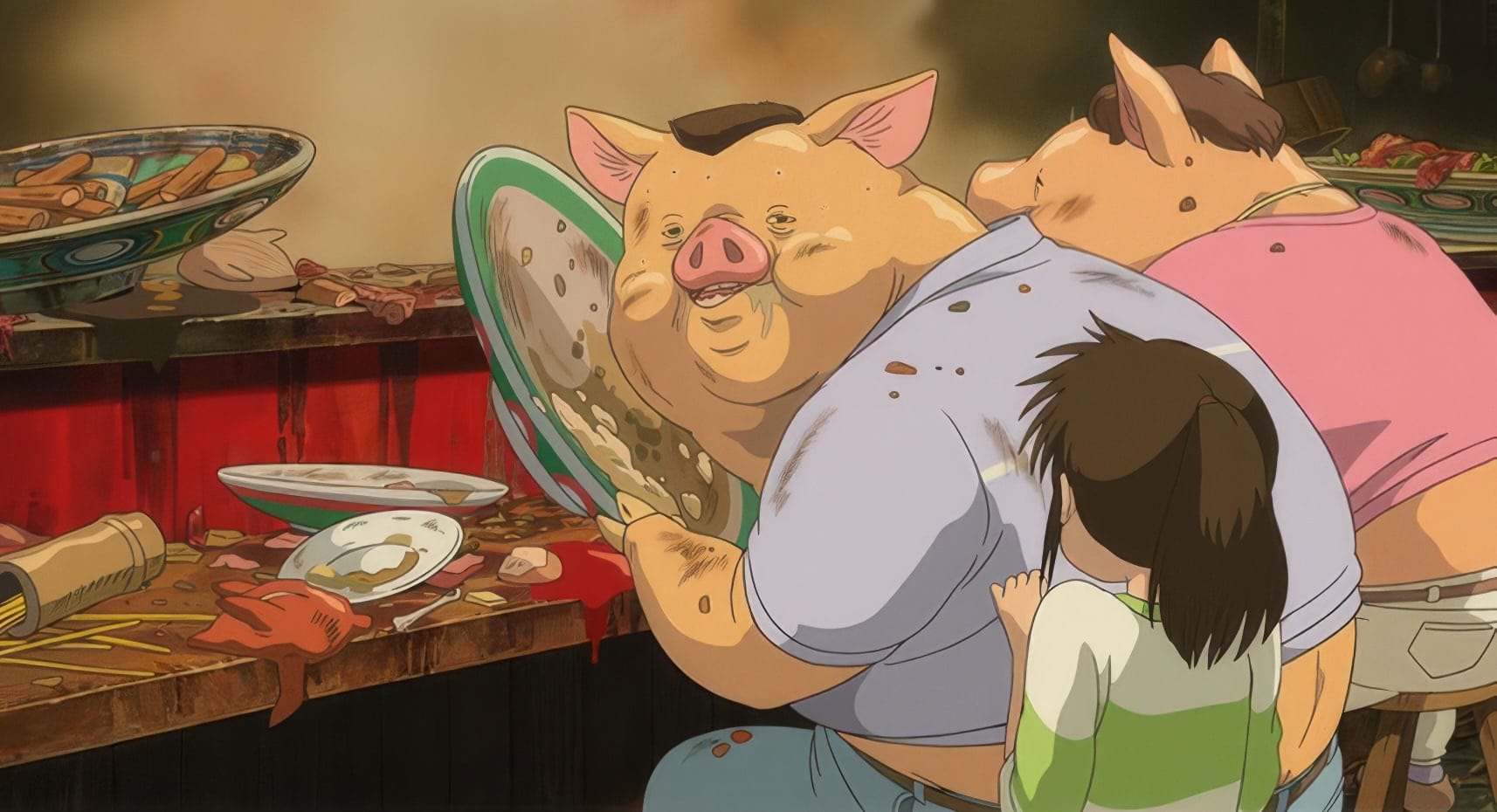

Food as Moral Compass in Ghibli Films

In Ghibli's universe, how characters relate to food reveals their moral standing. Remember Chihiro's parents in Spirited Away, greedily devouring the spirits' food and turning into pigs? That's 1980s Japanese bubble economy excess right there. Meanwhile, Sophie in Howl's Moving Castle transforms a chaotic castle into a nurturing home through cooking.

Princess Mononoke follows this pattern. Sharing food represents empathy and understanding. Taking or misusing food symbolizes moral corruption. Simple as that, yet profoundly effective.

What This Means for Modern Audiences

The food scenes in Princess Mononoke activate something deep in our collective memory – traditional rural life before industrialization, seasonal eating patterns connected to natural cycles, community-centered social organization, and spiritual relationships with food sources.

This isn't just nostalgia. It's cultural continuity anchoring identity in times of rapid change.

The film addresses modern anxieties about environmental destruction, social division, and loss of meaning while presenting traditional approaches not as backward but as wisdom. It shows how traditional values align with sustainability concerns, how traditional eating patterns offer health benefits, and how traditional practices provide refuge from modern pressures.

The Question Princess Mononoke Asks Us

Living in an era of food delivery apps and 24-hour convenience stores, we've perhaps lost something essential. We don't know who grows our food or how. Everything comes wrapped in plastic. The amount of food waste we generate is staggering.

Princess Mononoke asks: Is our relationship with food really so different from our relationship with nature? When Ashitaka shares his meal with Yakul, could we share that same respect with our environment? When Iron Town's people treasure every grain of rice, could we value our food similarly?

Why Ghibli Food Hits Different

Look, Ghibli food isn't special just because it looks delicious. In Spirited Away, when Chihiro's parents turn into pigs after their gluttonous feast, it's about human nature laid bare. When Sophie cooks in Howl's Moving Castle, she's literally transforming chaos into home through food.

Princess Mononoke works the same way. Sharing food opens possibilities for empathy and understanding. Misusing food reveals moral decay. These scenes work so naturally that you might not even notice the deeper meanings – and that's Miyazaki's genius.

Final Thoughts

Princess Mononoke's food culture is more than historical set dressing. It's Japanese traditional values meeting modern environmental consciousness at a crossroads, captured with incredible nuance.

Next time you watch Princess Mononoke, pay attention to those food scenes. Ashitaka and Yakul's simple meal, San's primal care, Iron Town's desperate need for rice... Each scene carries a message about connection, survival, and what we've lost along the way.

Ultimately, Princess Mononoke suggests that food isn't just fuel – it's the thread connecting nature and humanity, past and present, individual and community. And maybe, just maybe, respecting that connection is the first step toward a sustainable future.

Because sometimes the most profound truths come not from grand speeches or epic battles, but from the simple act of sharing a meal.